Historical Records Imaging Project

Slavery, Anti-Slavery

and the Underground Railroad

in Centre County, Pennsylvania

by Robert L. Baker

This article appeared in the March, 1999 issue of the Newsletter of the Centre County Genealogical Society. It is reprinted here by permission of the Society.

The recent disclosure of DNA tests on the progeny of Thomas Jefferson's slave Sally Hemmings with a link to our third president, along with last year's National Book Award winner Slaves in the Family by Edward Ball has raised some interesting questions about the existence of slaves everywhere and their role in that social entity known as "family."

A little-known but recently discovered series of documents found in the early Quarter Sessions records of Centre County reveals 14 instances in which persons of African American descent had their birth recorded. Although Pennsylvania had made a decision to abolish slavery as early as 1780 as late as 1820 Centre Countians were still registering blacks, if not as property, then as members of the family.

In other words, names like Antes, Benner, Boone, Harris, Miles, Rankin, Richards and Smith have an addition to their family tapestry that family historians and genealogists may have overlooked.

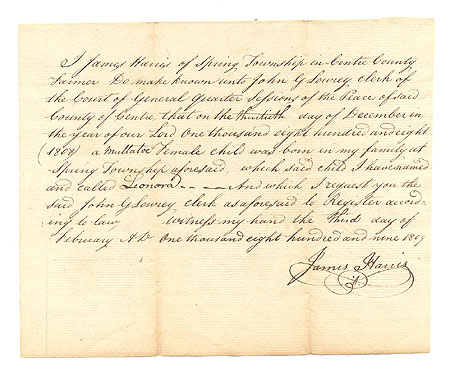

An example of the kind of thing found in the Quarter Sessions records is from the home of James Harris, one of the founders of Bellefonte, who incidentally inherited "my Negro girl Esther" in 1807 from his mother, according to her will proved in Mifflin County. An abstract of the Quarter Sessions record reads:

"I, James Harris of Spring Township in Centre County farmer Do make known . . . a mullatoe female child was born in my family at Spring Township, aforesaid, which said child I have named and called Leonora."

While it has not yet come to light as to when Leonora gained her freedom, perhaps some enterprising family historian can tell us a more complete story of what life was like at the Harrises.

We know from a Harris family genealogy nothing about Leonora, but we do know that Joseph Harris, a son of James and Ann (Dunlop) Harris, was quite the benevolent sort when he resided at the Howard Iron Works.

The story goes: "One of his servants at this time was a recently runaway slave, John Gray by name. While following Mrs. Harris who was riding to the village of Howard on horseback he was kidnapped and carried away. Mr. Harris made immediate efforts to locate the captors, but failing in this, sent Mr. Daniel Welsh to Virginia hoping to find John Gray at the plantation where he had formerly been a slave. There Mr. Welsh learned that he had been sold into Georgia, followed him there, purchased his freedom, and brought him back to Howard Iron Works, according to instructions."

While the South supported slavery until the end of the Civil War in 1865, Pennsylvania went on record as formally desiring to end slavery by passing a gradual emancipation law in 1780. The law stated that no African American born after 1780 in Pennsylvania would be enslaved past the age of 28. In essence, it substituted indentured servitude for slavery.

Interestingly, this law also mandated that children born to these indentured servants be registered and hence the Quarter Sessions records.

On the eve of the county's formation in 1800, James Cooke, who built a sawmill at present-day Spring Mills, was known to have owned slaves even though his name does not appear in these early Quarter Sessions records.

While in 1820 the last of the early records showed Frederick Richards of Bald Eagle Township referring to his servant Phillis "as a slave of mine," it's not clear how persons of African American descent were viewed by the public at large.

Certainly many viewed Central Pennsylvania as a safe haven for blacks, and in the late 1830s the St. Paul's African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in Bellefonte to provide for a place of worship. According to Charles Blockson in his 1981 The Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania, the church itself was a station on the legendary Underground Railroad.

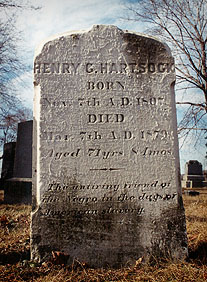

John Blair Linn's 1883 History of Centre County has suggested that Henry G. Hartsock of Patton Township and Rush Petriken of Bellefonte were the first two abolitionists in Centre County.

Of Hartsock, a tombstone in Gray's Cemetery says he was "The untiring friend of the Negro in the days of American slavery." Linn wrote of Hartsock that "runaway slaves seeking route to Canada ever found protection and aid at his home."

As to whether blacks in Centre County took on the surnames of the persons to whom they were indentured, authorities seem to agree that this did not happen to as great an extent as it did in the relationship of slave to master in the South. Yet, one of the longstanding black families of Centre County—the Deliges of Halfmoon Township—named a child A. Hartsock Delige, apparently in deference to someone in the Hartsock family, maybe even the ardent abolitionist.

The county is replete with rumors of many places that could have been hiding stations along the so-called underground railroad which was neither underground nor a railroad but rather a loosely constructed network of routes that originated in the South, intertwined throughout the North, and eventually ended in Canada.

One of them supposedly went through Centre County. The Linn House (left) at 133 N. Allegheny Street and the Thomas House (below, right) at 260 N. Thomas Street are two places in Bellefonte believed to have secret hiding places. However. documentation is practically nonexistent as it was a violation of the Fugitive Slave Law to harbor runaways.

That didn't stop people who felt there was a higher moral imperative from trying. Folks like William Thomas and his wife Eliza Valentine Thomas were ardent abolitionists and Quakers.

Perhaps no single religious group gave more support to the antislavery effort, although Methodists, Presbyterians and Baptists allegedly helped contribute financially to the efforts of St. Paul's A.M.E. church. The religious faithful no doubt contributed in other ways as well.

Regardless, Centre County must have been all abuzz in 1841 when Lucretia Mott of the American Anti-Slavery Association and herself a Quaker, arrived in Halfmoon Township as a delegate from the Friends Baltimore Yearly Meeting.

While her actual words have been lost to posterity, there were many who recalled the tenor of the times.

Myrtle Magargel wrote 100 years later that a Mrs. Mary Way told her, "Many a black man has been hidden in my father's barn and sometimes the slaveholders would come and work pitchforks around through the hay to find their slaves."

Way, whose father was Jesse Underwood. added that "the underground railroad wasn't talked around very much. Folks had to know who they could trust and be pretty sly. But lots and lots of runaway slaves hid in my father's barn at Unionville."

She added, "they were taken after dark in a closed carriage to the next station wherever it might be. Some were in Bellefonte and some in Halfmoon. The slaves came for the most part from the Ohio and Juniata Rivers. They travelled mostly by water."

Other underground railroad sites in Centre County have been rumored to be in Philipsburg, Lemont and even Walker Township. The current mayor of Bellefonte, Candace Dannaker, has some of these spots pinpointed in a paper she once did for a Penn State class.

On the eve of the Civil War, when the 1860 census showed Centre County to have 27.007 persons or about one-fifth its present population, some 163 persons were identified as black and 100 were identified as mulatto.

For many of the older persons enumerated, birth states such as Maryland and Virginia suggest a history on the move. After 1880, birth states of parents given on census records suggest an even more extensive travel past with some deep South states such as the Carolinas and Georgia just waiting to be untapped.

Records of the A.M.E. church and Quaker (or Friends) Annual Meetings might also shed some additional light on a tale of our past that is just beginning to be told.

Baker wrote this article in an attempt to begin understanding the family dynamics of his own ancestors John and Katherine (Whiting) Lane having had slaves in their Bedford, Mass, home before granting them freedom prior to the American Revolution.